The vision of the founding projects within Logos has always revolved around the concept of the “Holy Trinity,” the three fundamental components of decentralized infrastructure: Durable Storage, Ephemeral Messaging, and Consensus/Execution. An implicit assumption that came along with that narrative was that the implementations of these three pillars would be tightly coupled from the start, meaning that they would seamlessly interoperate with each other, or even be intimately intertwined in their underlying architecture. This document attempts to take a closer look at that assumption in order to determine whether or not it’s worthwhile to maintain. In turn, we can consider what that means for our Organizational Roadmap, the associated projects underneath it, and the broader ecosystem that collaborates alongside us.

These thoughts are a culmination of:

- Long-standing thoughts/concerns around the progressively divergent technical paths of the three projects currently under Logos: Waku, Codex, and Nomos

- The introduction and development of the zkVM project and questions around how collaboration/ownership should work with the Nomos project

- Conversations over time with other Core Contributors around these two topics, and peripheral topics, that involve “how the Org works and grows together.”

I’d like to note up-front that this is just a model and thoughts around it. The reality of how we move forward will be more subtle and a mix of all these options. So here goes…

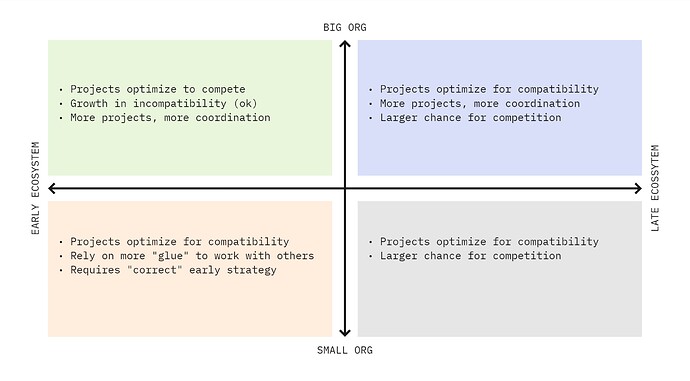

I’m looking at all of this by attempting to answer two key questions which create potential paths forward:

- “How big do we want to be?”

- “How early are we?”

The combination of the answers to these two questions sets the path forward for appropriate project strategy. “How big” sets the tone on how large we expect the Logos Collective to span w.r.t. the number of projects underneath it and the potential size of a given project. It also reflects the “investment appetite” of the Collective. “How early” helps us understand the maturity of the ecosystem, the expected innovation and growth throughout, and the rate of its expansion, for which we should prepare as best as possible.

A Mental Framework to Describe Things

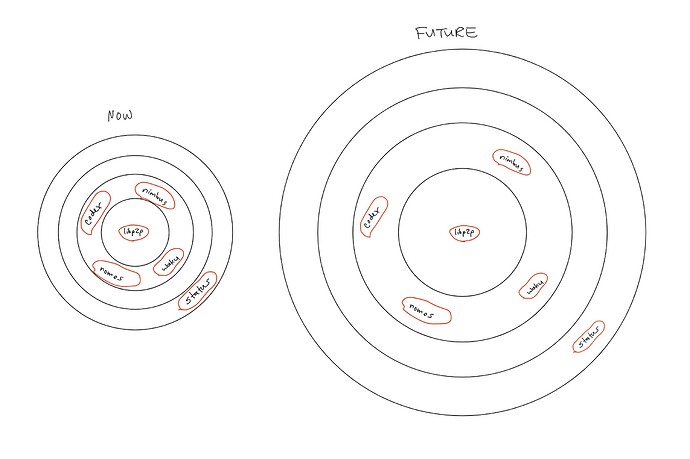

Putting it another way, let’s view the Logos/Status projects within the larger Web3 ecosystem as “bubbles” associated with various “tech stack layers.” These layers are to be seen as concentric circles with the center being the “deepest” in the tech stack, and the outer-most or highest layer being considered the “Application Layer,” which caters to software that actually interfaces with the “general consumer.”

The center of the ecosystem is considered “foundational technology.” It’s the groundwork that others build upon. Often in technology stack analogies and models it is referred to as “deep” in the stack. An important consequence of this positioning is that it suffers from the least external constraints, simply because it depends on less things. Each concentric circle as you move outwards depends on more and more things “below” it, thus inheriting the constraints that technology imposes. It is the end goal of applications to build products people want with the features and constraints of the technology available below it.

As the ecosystem grows and evolves, all of the circles grow (this is a rough approximation–we won’t get into all the possibilities for growth and how that’s shown in the circles’ relationships to each other). The projects within the circles also change, affecting their “representative space” within their respective layer and the ecosystem at large. In other terms, you can think about total ecosystem growth as a stressor to projects to which they need to react. They can either “expand” or “harden.” A hardening response of a project is an increase in specialization in order to continuously fulfill its role while an expansion response is to leverage a current working product to a broader audience. You can’t do both easily with the same resources.

This concentric circle analogy is also nice in that as the entire ecosystem grows, the rate at which the outer circles grow is larger than the rate of the inner ones, meaning that the potential total landscape of the application layer will grow faster than the potential total landscape of the infrastructure that supports it. This is just a math fact, but it ports nicely to our analogy. Fun side factoid: this breaks down as you increase “dimensionality” as the volume of a solid approaches the surface area as you increase dimensions.

Under that idea, note that the more foundational a project is, the more likely it is to be able to expand its footprint with the growth of the ecosystem (under the same resource input) because the need to innovate is less, thus you can serve a larger audience with the established tech you have.

This means that as the ecosystem grows and if our projects “stay the same size,” then the distance between it and other projects grows as well, eventually creating enough “space” for another project to sit between, operating as a glue. An example of this is what you see now in the “modularization” meta that’s happening across blockchain infrastructure, and then further specialization and tradeoff-optimizations that exist across the competing products. A company like Espresso Systems couldn’t exist in the Bitcoin era because the network was basically modeled as a distributed monolith.

Project Adaptation in this Model

If you visualize a given project as “taking up space” like a bubble within the ecosystem, and that bubble expands as the ecosystem expands, then various things can happen as a result of that expansion. Assuming the same amount of resources are applied to a project, they will need to specialize further or broaden their area of service. It is important to note that this is fundamentally a function of the industry and how it’s moving. The ability to broaden the bubble (assuming constant resources) means that their solution is ossified substantially in the ecosystem.

Now let’s look at our concepts through this model to see how things may be affected.

Big vs Small

This concept is asking ourselves “how much of the space within these circles do we want to occupy, and how much should we grow with the expansion of the industry?”

When the ecosystem expands, space is created that has potential to be occupied, which can be considered “open opportunity” within the ecosystem. That eventual occupation either comes from a project expanding its footprint or by new projects filling in the gaps. Is the org’s strategy to occupy key positions and maintain them (small), or to continuously grow and adapt with the ecosystem’s needs and opportunities (big)?

Early vs Late

This is a sentiment around “how much do we think the tech will change and grow” over time from here, or “how ossified is the tech”? If we’re late to the game, then underlying mechanisms are reasonably understood and in place which leads to lower risk in the coupling of differentiated projects. Basically, you’re less likely to identify a needed breaking change if things aren’t changing that much.

Furthermore, the “total space” of the industry doesn’t expand substantially from this point, thus leaving our understanding and “project coverage” to remain similar to where it is today, thereby allowing projects to remain “close” to one-another. This means the circles aren’t going to change in size or shape in any considerable way, and making bets on “how things fit together” has a lower risk of being wrong.

The alternative to this is that we’re early, and we expect the “ideal implementation” of a given project market to be far from the current State of the Art, which requires rapid innovation and experimentation to stay up with the bleeding edge. An appropriate strategy here would be to “settle” in strategically safe locations (the holy trinity) and figure out the “glue” as the ecosystem expands.

What’s the best long term alignment direction?

Here we discuss what each of these options means and the Logos strategy that is aligned with it. I’ve summarized a bit (grossly) in a punnett square below, but that won’t capture all the details we’ll go through (a lot of) them too.

Small and Late

We assume that the Logos Collective will not expand substantially compared to the total ecosystem’s landscape and that the current landscape is relatively slow in its growth from this point forward.

A cogent strategy under these assumptions means that we pick key strategic positions and dominate them with the resources at our disposal. Additionally, our positions that exist must work very well with one another. This is facilitated by the assumption that methodologies of interaction won’t change much anymore; focusing on interoperability won’t hinder our future needs to “stay up to date” with other optimizations associated within a specific domain. (i.e., our shit won’t break or become obsolete later because of interoperability choices we’ve made today.)

Small and Early

We assume that the Logos Collective will not expand substantially compared to the total ecosystem’s landscape, but we also expect that the ecosystem will expand substantially compared to how it exists today.

This reinforces the importance of the positions we choose to occupy, as the niche we occupy will need to provide enough value throughout the ecosystem expansion to warrant lasting relevancy. It also forces our value proposition relative to the entire industry into esoterism, unless we pick foundational positions that we believe will remain foundational.

As the ecosystem expands, the gaps between project positions will become larger. Our decision to remain “small” means that we need to be ok with other projects outside of Logos to serve as the glue, as the resources allocated to any given project need to be focused on “hardening” themselves to remain relevant in a changing world.

The consequence is a divergence in “collaborative ease” as projects align themselves with the best practices of their respective bleeding edges in order to stay competitive. In other words, you’ll need more glue to stitch projects together. You’ll also continuously reduce the likelihood that a method within one project can be seamlessly reused in another because they’re independently optimizing for different things.

Big and Late

We assume that Logos Collective will continue to expand its position within the broader ecosystem, and that we have a pretty good idea of what that looks like from here on out. Furthermore, things won’t change too much within the broader ecosystem and that the current landscape is relatively slow in its growth from this point forward.

Because we know how things work, the things we build should work together without much effort.

Big and Early

We assume that Logos Collective will continue to expand its position within the broader ecosystem, and we also expect that the ecosystem will expand substantially compared to how it exists today.

Because we are early, it is likely irresponsible to think that what the State of the Art looks like today will remain the same in the future, which mandates our ability to adapt and continuously evolve our products in order to stay competitive in their respective markets.

My Personal Opinions

I find us sitting firmly in an “Early” ecosystem but in the middle of a “Big” and “Small” organization, which will eventually be decided by available funding, the “Founders’ Vision,” and hopefully conversations that stem from this post.

I personally believe we’re “Big/Early” which has a few consequences. I’ll try and get to some of them down below.

The extension of the Logos Collective from Status was a precise attempt to establish key foundational positions lower in the stack. This is usually portrayed via the continuation of Ethereum’s “Holy Trinity” narrative (but with stronger privacy in our case). We believe that no sufficiently good decentralized application can be built without the main three pillars: Storage, Messaging, and Agreement/Execution. The Status Applications clearly stand within the application layer to consume that infrastructure as it becomes ready to give users an experience that is currently unavailable elsewhere.

It’s clear that there is overlap of functional requirements across these projects. For instance, Nomos needs distributed data availability and ephemeral messaging in order to work. Why not just use the other projects to do this? Seems like the obvious answer, right? But do the generalized private messaging decisions associated with the Waku roadmap make it too inefficient for the Nomos consensus mechanism (e.g. leading to too long of a time to reach a consensus decision)?

As we look at the rest of the org and various projects within it, and as the total ecosystem expands, we’re seeing a divergence in technical compatibility represented by a growing requirement of additional middle-ware that needs development. An example of this is the “chat” abstraction/optimization on top of Waku, to be consumed by Status for their more constrained needs. This work represents “a new bubble” in between projects we already have, and the subject of “who owns this work” has been a point of contention for quite some time along with the question, “what is it called?”.

Here are a few more examples of organizational difficulties around this topic:

- Technical alignment and coordination of Nescience (zkVM team within Vac) and Nomos

- Nomos exploring the creation a mixnet on top of

libp2pas opposed to relying on Waku protocols for network-level privacy - More generally, no Logos Collective infrastructure project (and Nimbus) using Waku for message passing

- Codex recreating an

ethers.niminterface to blockchains instead of using what’s been built by Status Desktop

It’s clear that we want applications to use these foundational infrastructure projects to serve users, but it isn’t clear how well the individual projects work with each other and how much room should be left in between them for “glue projects.”

If we are leaning towards an “early” ecosystem viewpoint, then a project that is attempting to live on the bleeding edge of their respective market should work to stay there and remain competitive, which means potentially making optimizations that move away from cross-project compatibility. That being said, when these things happen, it should have an explicit technical justification for such a move. This allows the in-between glue that will eventually be needed for cross-project integration to be better understood and planned for. These justifications, as far as I’m aware, don’t exist or are not easily identified if the question is brought up.

Another factor to take into account is that the further generalized a project becomes, the less immediately useful it is in an optimized instantiation, thus the further away it moves from the integration into a specific project that may require optimization for a niche purpose. In other words, a more generalized project makes the bubble it takes up in the ecosystem larger as it has more potential use cases, but it also increases all of the distances between itself and any optimized use-case, thereby requiring additional development or, worse, outright incompatibility.

If the approach is decidedly “Big/Early”, it seems reasonable to assume that foundational projects may not be directly compatible with each other over the long-term because of the choice to remain competitive and useful within their own domains. We need to be ok with their needing to be glue between them, and whether or not we also develop that glue is a question that remains to be answered and will probably be a case-by-base basis.

Other factors not considered here but are clearly important

This is already a long post and I’ve missed some probably very key points to this decision and alignment. To name a few:

- Individual business cases vs Logos mission

- Financial allocations

- Investment portfolio strategy

But it should serve a good starting point and language to continue the conversation. Please discuss: Tell me what I’ve gotten wrong, your opinion of how we should work and grow together, what I’ve missed, additional pros/cons, etc.