Anonymity in Decentralized File Sharing: Practical Limitations and Open Questions

This research was presented at the IFT research call, you can find the recording here. Here is a written form of that presentation.

In this research post, we look at existing anonymous communication protocols that are relevant for decentralized file-sharing/storage. Tor is obviously one of the most mature and used ones. We’ll use Tor to give a baseline understanding of onion routing and hidden services. Then, we will look at Tribler, another protocol that is relevant to anonymous decentralized file-sharing. It is a decentralized BitTorrent-style system that builds on Tor’s onion routing and hidden services. Finally, we will look briefly into mixnets, another approach to anonymity that offers stronger guarantees but comes with performance and other challenges/limitations, especially use applied to the decentralized file-sharing setting.

In summary, this document we will cover the following:

- Brief introduction to the concept of decentralized file-sharing.

- Brief background on anonymous communication.

- Tor’s onion routing and hidden services & their limitations.

- Overview of Tribler, how it works, how it is different than Tor, and its limitations.

- Mixnet architectures and how they may apply to file sharing.

- Summary of the limitations and open questions for future research.

The aim of this research was to build an understanding of the design space for anonymous communication protocols. This will guide the design of the anonymity layer of Logos storage. The ultimate long-term goal is to provide anonymous file-sharing & storage with durability (persistence).

Decentralized File-Sharing

Decentralized file sharing main goal is to distribute storage and bandwidth across many independent participants (peers) rather than relying on a central server. Peers communicate over a P2P network (e.g. libp2p) and any peer can act as a client (requesting data), a provider (serving/hosting data), or both.

Building Blocks

- Content addressing: e.g., CID

Instead of locating data by a url, content addressing locates data by “what it is” (a hash of that data). - Chunking + Merkle-Tree/DAG: Files/datasets are split into multiple blocks, blocks are hashed and linked using a Merkle tree structure, the root of such a tree serves as an identifier for the files/datasets.

file -> blocks -> hashes -> Merkle-tree -> root ID - Discovery (DHT / indexing): The main purpose of the discovery component is to answer “Who has this content?” and allow providers to announce that “I have CID x”.

- Transfer (P2P exchange): Once a peer knows who has the content (blocks of data), it needs a protocol to exchange this data i.e. download and upload blocks from multiple peers (possibly in parallel). In a decentralized setting the protocol needs to handle multiple challenges: churn, NAT traversal, bandwidth caps, block&peer selection, parallel downloads, and retries.

- Verification: every block fetched from peers needs to be checked to ensure that the data has not been tampered with. It is cryptographically checked (hash must match).

Typical flow

- Publisher adds file → chunks it → gets content ID (hash/root).

- Peers announce availability (“I have CID X”).

- Downloader searches network for providers (“who has CID X”).

- Downloader fetches blocks from many peers + verifies hashes.

- File reconstructs locally from verified blocks.

Challenges

- Performance: Latency depends on peer availability, churn rate, and routing.

- Persistence and availability. In some use-cases, the data stored in the networks needs to persist over some specified period of time, and to achieve this, the common approaches include: pinning services, replication, providing incentives to peers (monetary and interest-based), and audit/proofs to ensure data durability.

- Anonymity & privacy risks (who requests/provides what)

As you probably guessed from the title, we’ll explore the Anonymity & privacy challenge in this post.

The Privacy & Anonymity Challenges

Decentralized file-sharing as we mentioned earlier requires discovery + connection + transfer and each step can leak metadata:

- Interest: which content IDs (e.g. CIDs) you query the DHT or request from peers.

- Provider: which peers are hosting specific content (referenced by their CID).

- Network identifiers: IP address, peer IDs which are visible to network observers and other (possibly malicious) peers in the network.

- Social graph signals: repeated interactions can reveal communities/relationships.

Solution space

There are two broad directions, depending on what you are trying to hide:

- Network-layer hiding (who you are)

Onion routing (Tor, Tribler).

Mixnets. - Private discovery / content hiding (what you want)

Private DHT lookups (query obfuscation, recursive/iterative lookup).

Private information retrieval (PIR) for provider discovery (ask without revealing the CID)

We’ll focus in this post on Network-layer hiding, and possibly explore the other in the future.

Privacy and anonymous communication

Privacy is a general term and so it is important to define a threat model for the protocol and what privacy properties are needed or aimed for. The most common privacy properties that are often desired for a data storage/sharing system would be:

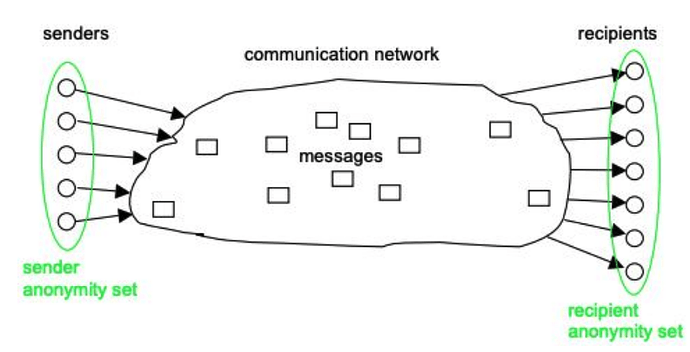

- Anonymity: sender & receiver anonymity which is formally defined as “The state of being not identifiable within a set of subjects, the anonymity set.”[1]

- Unlinkability: linking 2 msgs/actions to a single user

- Unobservability: having knowledge of whether or not a user performed an action

- Undetectability: inability to determine participation in the network.

- Confidentiality & Integrity: of the data

- Distribution of trust: avoid centralization (failure & compromise)

There is no single system that would provide all these properties, and most aim to support a subset of them to meet their threat model.

In terms of anonymous communication, there are various assumptions that can be made about the adversary. The adversary can be assumed to be:

(1) a passive entity that collects information from other users in the network.

(2) An active entity that doesn’t follow the protocol specification and attempts to inject, delete, or modify network traffic.

Additionally, as can be seen in the image, the adversary can be:

- In the outgoing traffic,

- In the incoming traffic,

- Global: observing or controlling the whole network,

- Part of the sender/receiver anonymity set.

Another assumption that we usually make is that the adversary cannot break the crypto primitives used in the protocol.

Tor, Tribler, and Mixnets Threat Models

Tor assumes “an adversary who can observe some fraction of network traffic”. This adversary can:

- Generate, modify, delete, or delay traffic

- Can operate onion routers of his own

- Can compromise some fraction of the onion routers

This threat model is a relaxed version of the one often used for mixnet where the adversary is assumed to be a “global passive adversary”. This means that Tor weakens its anonymity guarantees for the sake of low latency. This is intentional since Tor want to remain usable for most use-cases, most commonly browsing the internet.

Tribler’s threat model is not specified clearly. We can assume a threat model that is similar to Tor (because it uses “Tor-inspired” onion routing & hidden services), however, it is much weaker than that based on their own statements. In its current state, Tribler only protects against censorship and “copyright-enforcement”.

Onion Routing

In this section, we give some background on how onion routing works, specifically the one Tor uses and specifies in the Tor specs. Tor uses persistent 3-hop circuits: (1) guard, (2) middle, (3) exit and we will use these names throughout this section.

To establish a circuit of 3 relays, the client needs to select 3 relays from the Tor directory. Directory authorities (think of them as cert authorities or servers that maintain and serve signed directory/document) publish a signed list of relays. They reach a consensus by collecting enough signatures.

The Tor client fetches the directory and selects the relays based on the flags as specified in the specs. Then, builds the circuit path step by step with CREATE/EXTEND, negotiating keys on each hop.

Client --> Guard --> Middle --> Exit --> Dest

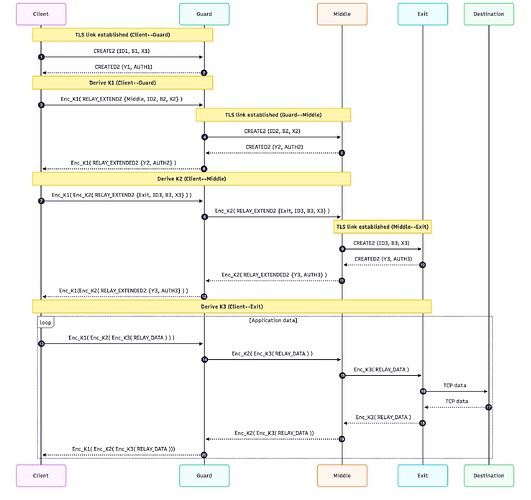

The full workflow is illustrated in the following sequence diagram:

Let’s break down what happens when the client builds the circuit.

First the client selects the 3 relays (guard, middle, exit) from the directory so the clients know their public keys. Then the client starts by sending CREATE2 to the guard node to initiate a connection.

Client --(CREATE2)--> Guard

The guard responds with:

Guard --(CREATED2)--> Client

What happened here is that through these messages the two are now connected, have a known circuit id, and shared encryption keys (2 symmetric encryption keys, one for forward traffic and one for backward, keeping it direction-separated)

Now the Client must extend this circuit so that it goes from the guard to the middle node. To do this, the client sends an EXTEND2 msg to guard which instructs it to basically send the CREATE2 to a middle node that the client specified in the msg. Meaning that it will follow the same previous step:

Client --(EXTEND2)--> Guard --(CREATE2)--> Middle

The backward traffic:

Middle --(CREATED2)--> Guard --(EXTENDED2)--> Client

What is happening here is that the guard now creates a connection and performs the ntor handshake (for the encryption keys) on behalf of the client. The EXTEND2 contains the address&port of the middle as well as the client’s onionskin which contains client’s ephemeral pubkey. I mention this because it is important to note that the guard doesn’t do the handshake itself (i.e. doesn’t share the encryption keys with the middle), the guard only relays. However, the guard knows the address of both the client and the middle point, so it knows these two nodes are communicating, but that is not an issue in the big picture.

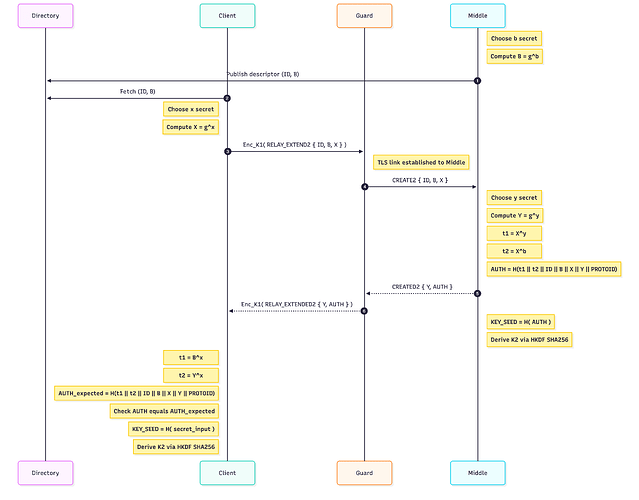

The ntor handshake is basically two DH handshakes as seen in the diagram below. Note that the second DH handshake (using Y) is done to achieve forward security. The diagram below is a simplified version of the ntor handshake, see ntor-v3 specs.

The last step the client needs is to do one more extension to the circuit to reach the Exit node. To do this, it has to hide the EXTEND2 from the guard but reveal it to the middle point, so the client hides this as a normal Tor payload that the guard needs to relay. A normal payload is a layered-encrypted package. For this step the payload would be:

payload := Enc(Kf_g, Enc(Kf_m, [EXTEND2]))

So once this payload reaches the middle node, it will understand that it is an EXTEND2 and basically do the same process as the prior step.

Client --Enc(Kf_g, Enc(Kf_m, [EXTEND2]))--> Guard --Enc(Kf_m, [EXTEND2])--> Middle --(CREATE2)--> Exit

The backward traffic:

Exit --(CREATED2)--> Middle --Enc(Kb_m, [EXTENDED2])--> Guard --Enc(Kb_g, Enc(Kb_m, [EXTEND2]))--> Client

Where kf_g and kb_g are the forward and backwards keys shared between client and guard, and kf_m and kb_m for the middle.

Once the circuit is set up as described above, the traffic is then encrypted in layers with the forward traffic Client --> Dest being:

payload := Enc(Kf_3, Enc(Kf_2, Enc(Kf_1, data)))

Where kf_n refers to the forward key and n is the hop number.

The backward traffic Dest --> Client is then encrypted at each hop i :

payload := Enc(Kb_i, data)

Where kb is the backward key.

Note that the layered-encrypted traffic carries fixed-size “cells” according to the Tor specs.

Some questions that might arise here:

-

How are the keys hidden from the guard when extending?

Because thentorhandshake runs between the client and the target hop (middle/exit) using that hop’s long-term public keys (obtained from the public directory authority). Theonionskinthe guard relays doesn’t let it compute the shared secret basically because it doesn’t know the secret key associated with hop’s pubkey. -

If the guard does the extension on behalf of the client, doesn’t the middle know the client because it is doing the handshake with its public keys?

The client’s ntor public key is ephemeral and unauthenticated, i.e. it doesn’t identify the client and not listed publicly nor do they need to be. The relay public keys on the other hand are listed in the directories. -

Can the middle tell it’s the second hop because the peer looks like a Guard?

It can tell who its peer relay is and it can look up that relay’s flags in the directory consensus (e.g. that peer has theGuardflag). So I think the middle can infer “my previous hop is a relay that’s flagged to be a guard.” However, I think that isn’t an issue because many relays with theGuardflag also forward other relay traffic.

Hidden Services

The basic idea of hidden services is to allow a host to serve data (e.g., a website or a bittorrent file) anonymously. In Tor, onion services publish descriptors (service keys & intro points) to hidden services directories (HSDirs), again these are centralized/federated with consensus. Clients fetch the descriptor, contact an introduction point, and both sides converge on a middle point also called “rendezvous” point. This forms a 6-hop circuit. No party learns the other’s IP.

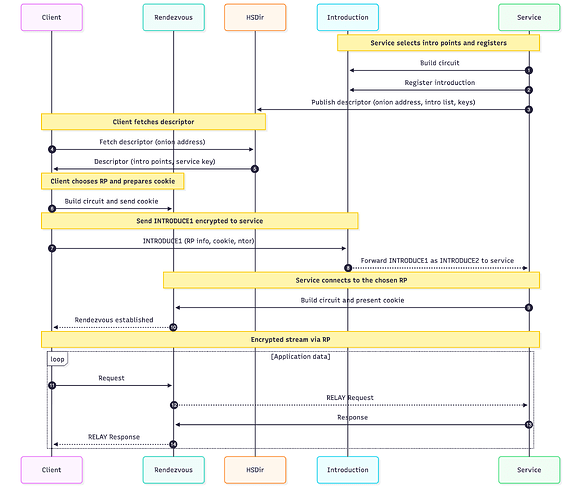

The hidden services protocol is a bit long to describe as can be seen in the diagram below, so bear with me.

Let’s say we have a hidden service called HS that would like to serve clients anonymously, i.e. neither HS nor the client know each other. Using the hidden services protocol (now called onion services), HS can provide the service without an exit node. Instead of the 3-hop circuits, the two meet at a Rendezvous Point (RP):

Client -> (3 hops) -> RP <- (3 hops) <- HS

The protocol to achieve this can be split into multiple steps/phases so that it is easier to understand.

Phase 1: Create intro points

HS picks 3 random relay nodes to serve as an intro point, and then builds circuits to these intro points:

HS --(3 hops)--> Intro1

HS --(3 hops)--> Intro2

HS --(3 hops)--> Intro3

Once these circuits are created, HS establishes the intro point:

HS --(ESTABLISH_INTRO)--> Intro_i

Intro_i --(INTRO_ESTABLISHED)--> HS

The result of this is that the intro points agree to relay traffic to HS over this circuit. Note here that the intro points don’t actually store any descriptors for the service that HS is providing, it only stores what is called AUTH_KEY. When HS establishes the intro point, it registers this authkey and then any intro requests (from clients) are relayed to HS if the authkey matches. See the intro specs for the full content of these messages.

Phase 2: Publish descriptor

Once the intro points are established, HS publishes the descriptor for the service on (multiple) HSDir which maps the descriptor to a set of (usually 3) intro points. Now this descriptor contains:

- Intro points + their onion keys

- Auth_key for each intro point (so that intro points can route your traffic to HS)

- enc_key which the HS

ntor. The client can then use it to do the handshake with HS.

This descriptor is encrypted twice:

- Once to hide from malicious directories (HSDir). The key for this layer of encryption is derived from the

.onionaddress which contains the service’s public identity key, meaning if you have that address, you can decrypt the first layer. - The second layer of encryption is only done when there is client authorization, otherwise it is not encrypted.

The onion address is then shared with all clients out of band. It could also be publicly available if there is no client authentication.

Note on anonymity:

- The intro point knows it is an intro point to a service and to map requests to that service it uses the auth_key. Now can the intro point figure out what service it is serving as an intro? It seems to depend on whether the intro point can find or see the

.onionaddress and whether the service has client authorization enabled on the descriptor. If the.onionis public (posted somewhere on the darkweb for example) and no authorization on the client then in theory the intro point can decrypt the descriptor and match the auth_key with the one it has.

Phase 3: Client looks up the descriptor

Once the client gets hold of the .onion address, it fetches the descriptor from the HSDir. It decrypts the first layer using the onion address and if there is client authorization, it decrypts the second layer.

From the descriptor, it learns the intro points and auth_keys, along with some additional data needed for the handshake.

Phase 4: Client chooses a Rendezvous Point (RP)

The client chooses a random relay node and builds a 3-hop circuit to it.

Then the client establishes RP and includes a cookie:

Client --(ESTABLISH_RENDEZVOUS(cookie))--> RP

Note that this cookie is just a random value that the RP will use to match HS with the client.

Phase 5: Client goes through the intro point

The client chooses a random intro point from the list obtained from the descriptor. The client first has to build yet another 3-hop circuit to the intro point and send an introduction request:

Client --(INTRODUCE1{to HS, auth_key, etc...})--> Intro_i

Intro_i --(INTRODUCE2)--> HS

Inside this request the client includes (encrypted so the intro point can’t see):

- Rendezvous point address/info

- the cookie to use when reaching the RP

- The client’s ephemeral pubkey material for the handshake through RP

Phase 6: HS connects to RP and then client

Once the HS receives the INTRODUCE2 msg, it has enough info to connect to RP. Of course HS must first build 3-hop circuit to RP and then connect:

HS --(RENDEZVOUS1(cookie, ...))--> RP

RP --(RENDEZVOUS2)--> Client

Now the two are connected, they do the handshake and agree on shared keys. Then data flows through the 6-hops:

Client -> GuardC -> MiddleC -> RP <- MiddleS <- GuardS <- HS

Tor Tools

There are a few tool that the Tor network provide:

- Arti: Modular Tor rust client, which one can use to plug-in onion routing and hidden services to any desired application. see our experimentation with Atri here

- OnionShare:

- Spins up a temporary Tor onion service on your machine

- Share a secret “.onion” url with the recipient (and optional key if auth is needed)

- The recipient connects via Tor as a normal hidden service client

- The transfer is just HTTP over Tor (6 hops)

- OnionSpray: Turns public websites into onion/hidden services.

Tor Limitations

Tor’s onion routing and hidden services can serve as an additional anonymity layer to a decentralized file-sharing protocol, however, it is important to note their limitations:

-

Tor protects against local adversaries/observers (ISP or destination).

-

Not a separate file-sharing protocol, so speed depends on Tor.

-

Centralized components: directory authorities & hidden services directories.

-

BitTorrent-over-Tor is a bad idea:

Tribler is faster in downloading a bittorrent file, but that is actually because Tor is not intended for downloading bittorrent and Tor’s exist nodes tend to block it (you can still get around it with a few tricks). It is actually NOT recommended to use bittorrent over Tor for multiple reasons which I can quickly list here (these are Tor’s arguments):- It breaks anonymity in practice. Many BitTorrent features use UDP (DHT, UDP trackers) and would leak your real IP in tracker announces or peer handshakes.

- Torrent clients have been observed to ignore proxy settings or include your IP in tracker announces/handshakes, so running them through Tor wouldn’t help with privacy ref.

- It overloads the network and puts legal risk on exit nodes.

Tribler

Tribler uses its own version of onion routing and hidden services (they call it hidden seeding since it seeds a bittorrent file) which is slightly different than Tor, but nonetheless results in significantly different anonymity guarantees.

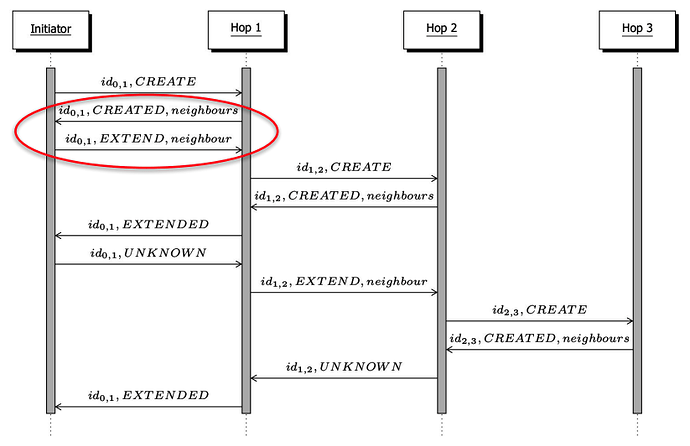

Tribler onion routing

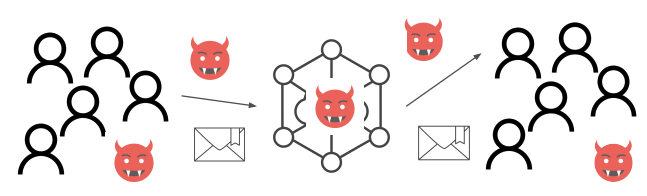

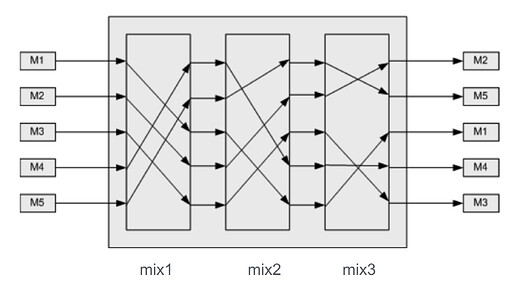

Tribler’s main difference lies in the way the circuit is created. It is actually illustrated in the image they have in their specs:

As we can see above, the circuit creation relies on each hop to tell the previous one what its neighbors are. This is because Tribler refuses to have Tor-style “centralized” directory authorities (For the sake of decentralization), so instead of getting a list of relays from a trusted directory, you learn the network by randomly “walking” it. The main limitation that led to this is NAT traversal. The client creating a circuit cannot ensure that hop2 for example can be reached by hop1 since hop2 can be behind NAT and in doing NAT hole punching you most likely would reveal the client IP. This is different than Tor’s centralized/federated directory authorities which the user (circuit initiator) can use to select a set of relays with reachable public IPs to build the circuit. Tribler removes the centralized directories and replaces them with an IPV8 version of DHT, basically allowing any node to serve as a relay. This also makes it vulnerable to Sybil attacks. Meaning that any node can cheaply spin up many malicious relays. So the odds of an adversary landing on multiple hops (and doing traffic correlation) go up.

As seen in the image above, the first step in building a circuit is selecting the first hop. The client (initiator) has to first randomly walk the network using IPv8’s (their own overlay) peer discovery:

- You contact some neighbor (or bootstrap servers).

- That neighbor “introduces” you to other peers by sending you their addresses, and might also do NAT hole punching between the two of you.

- You repeat this to find more peers.

- You select one random peer as the first hop

- You extend as seen the image by asking for that hop’s neighbours.

This design as it is now seems to be vulnerable to what is called “route fingerprinting” or “route capture”. In this attack, a malicious node can keep “recommending” only its malicious/colluding nodes (or other nodes in its control) for the next hop. This is a known weakness in earlier P2P anonymity systems like Tarzan and MorphMix. Basically, if you are unlucky to pick a malicious relay as your first “guard” relay, then you lose all the anonymity guarantees from onion routing because that malicious relay is controlling all 3 hops.

This is the main issue with Tribler and the reason for their statement: “decentralization weakens security”.

They could in theory solve this issue with a better peer discovery mechanism and NAT hole punching but we assume they don’t have the resources to research and implement this. Of course a perfect discovery mechanism that supports unbiased random sampling from the set of nodes doesn’t exist, but there are better ways of doing peer discovery.

Aside from this main issue, the following contain some additional limitations:

Exit nodes

Tribler is incredibly reliant on its exit relays. If you recall, the purpose of Tor’s anonymous download is to, well, download bittorrent files and so the user builds the onion circuit to an exit node and then that exit node has to then act as a normal bittorrent peer and interact with the bittorrent network to download the file.

There seems to be a scarcity of exit nodes and they are congested based on the MANY reports on their forums about how slow Tribler is. This is not entirely unexpected since running an exit node is a legal risk since the exit is the one that the public bittorrent network thinks is “actually” downloading the files and these files might not be so legal. Of course this is not the case for non-exit relays, these are somewhat safe. By default, every Tribler user runs a relay node but not an exit relay, for that you need to change the settings which makes sense.

Another problem with the exit nodes is that ISPs tend to blacklist them, which disable anonymous download (most recent ISP blacklisting is Oct/Nov 2025*)

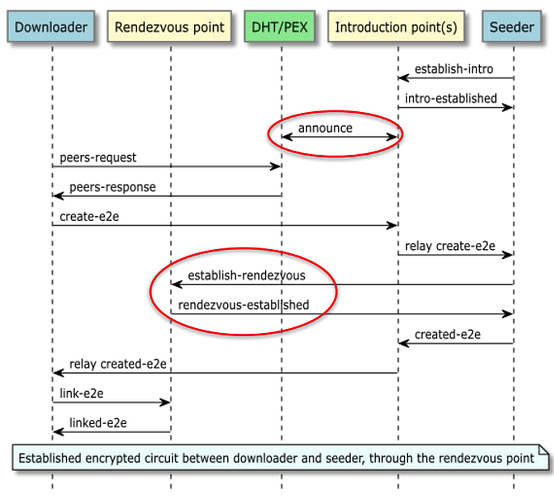

Tribler hidden seeding

Tribler modifies hidden services so that the service provided is actually a bittorrent file seeding/upload, and so you have hidden seeding as a result. It only works within the Tribler network, not on public bittorrent, i.e. an outsider with a magnet link cannot use it to download the file, you can only download it through Tribler’s anonymous download.

Again, Tribler removes the directory authorities (and HSDirs) and replaces them with DHT where nodes can query the service metadata. So the DHT would then contain the hidden service identifier and public keys of the introduction point. They mention that both downloader and seeder query the DHT over a circuit so that they don’t leak what the downloader wants to download, especially since the info hash for the bittorrent is the thing you lookup/query the DHT.

Overall, Tribler’s hidden seeding is pretty straightforward and follows Tor’s hidden services with some changes which will be discussed next. Here is the figure they have on their specs page:

From the figure we can see a few modifications:

- The introduction point announces the infohash to the DHT, i.e. it announces that it is an intro point for that infohash. Meaning that if you control the intro point, you can censor the data and it also exposes the intro point to DOS attacks.

- The seeder picks and creates the RP not the downloader, which flips how Tor does it. There is a slightly higher risk. Because the seeder picks the RP, a malicious seeder can bias that choice toward an RP it operates or that colludes with it. That doesn’t deanonymize you by itself, but it increases the chances of successful traffic-correlation if the attacker can also observe or influence your entry side. In Tor, the service doesn’t get to bias RP choice, so it must “get lucky” that you pick a malicious RP, in Tribler, a malicious seeder doesn’t need luck.

Aside from these modifications, I observed the following limitation:

- The current implementation requires every exit-node (the last hop of a circuit is called an exit node even if it doesn’t exit to the public BitTorrent swarm) to be “connectible”. “Connectible” here means: can accept inbound UDP from the overlay without extra steps ( port-forward/UPnP or hole-punching). This guarantees the intro point can be contacted reliably, but also concentrates this role on a subset of nodes → more attack vectors.

Incentives & Tokenomics

Tribler’s initial version and paper highlight the social aspect and incentives. This seems to be a core part of Tribler. However, they seem to have multiple designs for how this might work. Over the years, they produced many different designs including BarterCast and Trustchain.

Tribler’s struggled with getting the incentives right and to their credit it is a difficult problem to solve. Let’s look at the old design to understand the core problems with bandwidth incentives.

New users are given X GB worth of tokens (e.g. 20GB), but that can be used up very quickly especially if the user intends to use anonymous downloads. If the user downloads 6.67GB over 3-hops that’s enough to use all 20GB. Then once you use up all your balance and become a negative balance user, Tribler calls you a “selfish” client. Tribler down-prioritizes what it calls “selfish” clients and you get slow downloads. So what ends up happening is that users will either: (1) use 1-hop instead of 3 to save tokens, (2) reset Tribler and create a new user to get another 20 GB worth of tokens. Both of these options are bad for the system in general.

Then there is what Tribler calls “token blackholes”, where the bandwidth tokens get accumulated too much at the exit nodes because they are the ones serving most bandwidth. The exit nodes are usually not users and so they just have large sum of tokens that never circulate to normal users.

There is this cycle of: users not using 3-hops because it is expensive (sucks up their bandwidth limit) and then even if you become a relay to serve and get tokens, you don’t get much because users are not using relays and going directly to the exit. So for users it is difficult to get tokens, well aside from just creating a new identity which is easier. The winner with most tokens seems to be the exit node in this setup, but again it has to face some legal risk.

Search

For searching Bittorrent files, they propose different approaches:

- ContentSearch

- Tribler: P2P Media Search and Sharing

- SwarmSearch: Decentralized Search Engine with Self-Funding Economy

The idea in general:

- You query with some keywords to try to find content.

- You search your local cache first which contains torrent descriptors that your node learned from previous sessions.

- If not found locally, you query peers that advertise having a large cache of torrent descriptors, and they return the result if they have it.

- They rate-limit the searches, 10 per node lifetime searches.

The recent SwarmSearch (not implemented yet) apparently aims at using AI for search and ranking + incentives.

Mixnets

Mixnets are anonymous communication networks that are designed to provide strong anonymity guarantees against global network adverseries. Unlike Tor and tribler which focus on low-latency, mixnets introduce delay and possibly cover traffic to break correlations between input and output.

Chaum Mix

The original design was introduced by David Chaum, the so called “Chaum Mix”. The design idea is simple: A mix relay collects messages from many senders, shuffles them, and forwards them such that an observer cannot reliably link inputs to outputs.

Unlinkability is achieved by correlation of input and output based on:

- Message contents (protected by encryption).

- Size (often normalized by padding / fixed-size packets).

- I/O order (messages are shuffled/reordered).

- Timing (messages are delayed and released in batches).

Multiple mixes with layered encryption:

In practice, messages traverse multiple mixes, each removing one layer of encryption. This way, no single mix learns both where a message came from and where it ultimately goes.

Mixnet designs:

There are multiple mixnets designs which mainly differ by how they release incoming traffic. Common approaches include:

- Timed mixnets: Collect and flush after time T, or flush after N msgs arrive.

- Continuous-time mixes: Delay each msg individually with T time drawn from an exponential distribution.

- Pool mixnets: Flush a subset (random) of collected msgs, keep the rest for next round.

- Dummy Traffic: Dummy msgs generated (by users or mix) to confuse the attacker. The downside of this bandwidth overhead.

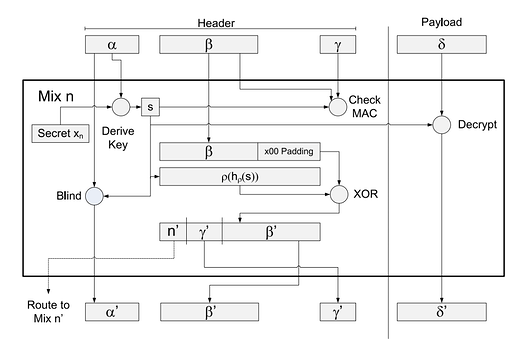

Sphinx packet

Sphinx is a widely used packet format for mixnets that provides: layered encryption, encrypted route information, and integrity of the packet (and routing) information.

Components:

- α (Alpha): ephemeral pubkey used to derive per-hop shared key.

- β (Beta): encrypted routing information (the header that tells each hop where to forward next).

- γ (Gamma): MAC to ensure header integrity.

- δ (Delta): The payload, encrypted in layers.

Flow (at each hop):

- Derives the session key from α

- Verifies the header integrity using γ

- Decrypts one layer of β to extract the next hop.

- Decrypts one layer of δ

- constructs a new packet with updated values of α, β, γ, and δ.

- Forward to the next hop.

Single-Use Replay Blocks (SURBs)

Sphinx is often extended to support Single-Use Replay Blocks (SURBs). SURBs are a mechanism (included in Sphinx headers) that let someone send a response back along an anonymous route chosen by the original sender and are often used once only.

SURBS can be used for:

- Replies,

- Acks,

- Can act like an “anonymous return address” (sometimes compared to a hidden-service style identifier, with important differences depending on the system)

Mixnet attacks

There is plenty of literature on existing attacks on mixnets. We won’t cover all here, but we highlight one classic example: “N-1” attack.

Steps:

- Empty mix of real msgs

- Wait for the target msg to arrive

- Fill the mix with dummy attacker msgs

- Attacker sees where the output target msg goes

This is easiest against naive batch designs and low-traffic settings, but there are more sophisticated variants.

There are many more attacks in literature that we won’t cover in this research post.

Mixnets & Onion Routing - Similarities & Differences

Mixnets and onion routing share some core ideas, but target different threat models and performance goals.

Similarities

- Routing by the source/sender

- Layered encryption/ public key cryptography

- Overlay network

- Multiple hops

Differences

- Onion routing is connection-based, persistent circuits, while mixnets are packet-based.

- Mixnets add latency (and dummy traffic).

- Threat Model:

- Onion routing: Local adversaries/observers (ISP or destination).

- Mixnets: Global adversaries/global traffic analysis.

Open Questions and Directions for Future Work

In general, both Tor, Tribler, and mixnets target different threat models and result in different latencies. Tribler is specifically targeting anonymous download and seeding of Bittorrent files, however, it does have limitations as described above (possibly more hidden in code for future research to be done). In deciding which protocol to use, the following must be considered:

- What privacy properties are needed?

- What is the target threat model and required anonymity guarantees?

There are multiple open questions for Future research, which we aim to explore:

- Do you make privacy opt-in or mandatory for all? How to avoid “small anonymity set” for private users?

- How to deal with the “bootstrap problem”? i.e. the need for a sufficiently large anonymity set.

- How to balance anonymity and efficiency?

- How does privacy interplay with durability (persistence)? And how would an anonymous remote auditing scheme look like? How does durable storage/replication affect metadata leakage?

- How would incentives, tokenomics and payments work in the anonymous setting?

- Can the mix protocol be adapted to work with a persistent circuit (for low latency) and provide hidden services?

- How to move from centralized directory authorities → DHT? needs Sybil resistance and DOS, unbiased circuit path selection.

- How to employ some kind of rate limiting (e.g. RLN or PoW)? Rate-limiting for access to hidden services?

- How to manange Network churn and provide a usable experience? Can multi-path circuits be used?

- Since NAT traversal can reveal public addresses, how to design the circuit path selection and hidden service to avoid leaking client and service IPs?

References and additional resources

- Tor Specs

- Tribler Wiki and Specs

- A Survey on Routing in Anonymous Communication Protocols

- A Formal Treatment of Onion Routing

- Bittorrent over Tor isn’t a good idea

- Tor: The Second-Generation Onion Router

- A Formalization of Anonymity and Onion Routing

- Proving Security of Tor’s Hidden Service Identity Blinding Protocol

- Arti Tor rust client

- onionShare